Indeed we’ve been blessed this cool season by some good rains in the Sonoran Desert–and everywhere there is greenery popping up. Weeds, you say? Let’s take a closer look! As our SavorSister Amy shared earlier this month in her tasty “rocket post”, what may LOOK like weeds are actually the gift of wild greens! Tia Marta here to share more ideas for wondrous weed-collecting.

This sweet 4-petaled “Arizona jewel plant” also known as “silverbells” (Streptanthus carinatus), is an endearing wild native mustard with delightfully good taste and nutrition. Planting silverbells seeds can also make a delicate addition to your own edible landscaping.

Out in the desert and in town you can find great patches of silverbells right now, especially in the shade of other desert shrubs. At times like these when there is such plenty (with thanks on our lips for these edibles), we can feel some assurance that harvesting a little for our family will still leave lots for other desert creatures and seeds for a future winter.

Silverbells isn’t spicy–no picante bite like the introduced London rocket or mature arugala–…and every above-ground part is flavorful —fresh right off the plant!

To my palate, its symmetrical little urn-shaped flowers even have a slight sweetness.,..

A taste of its flower can be like a communion.

Silverbells’ near-succulent leaf is a perfect addition tossed fresh in a salad. You can see the thickness of the juicy leaf in this cross-section view.

….And silverbells’ young green pods are delectably, “vegetally sweet.” Enjoy them fresh and raw, because, (alert!), with stir-frying the pods suddenly become bitter. They’re best used fresh to bedeck a salad.

Silverbells is a Brassica, that is, in the cole-family of highly nutritious vegetables. Besides in a fresh mixed salad, my favorite way to enjoy their nutrition (high Ca, vit.A and C, folates) is in a veggie stir-fry. I have added the greens last in this tofu stir-fry. Can you spot the silverbell flowers I topped this dish with?

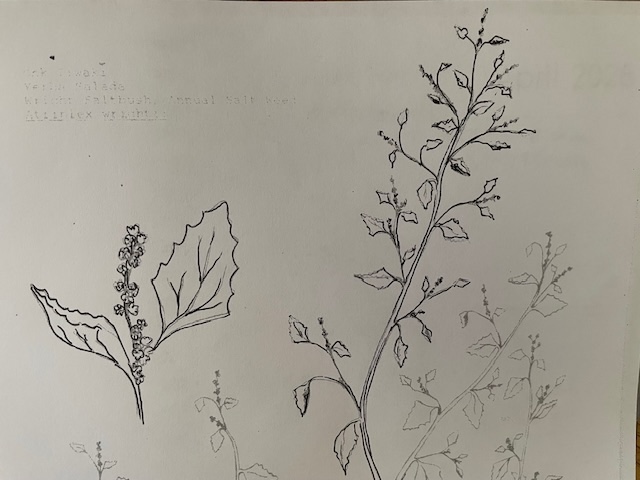

Here’s another “weed”–my very favorite, but very rare–which my O’odham mentor showed me years ago–opon i:wagĭ. Known in Spanish as patota, and in English by the truly misleading term “poverty weed,” it only comes up in certain years with winter rains at just the right times and in right amounts. She led me to harvest in corrals and roadsides on the poorest soils, and there appeared these patches of flat-lying rosettes of small thick leaves, so unassuming. Not very noticeable but worth noticing!

This season, see if you can find some opon i:wagĭ out there in degraded sandy soils! It is easy to dig up the whole plant. Cut off its tap root and steam the little green spinach-like leaves. The best dish my teacher ever cooked for us was opon i:wagĭ fried with i’itoi’s onions in a little bacon drippings. I thank her in my heart for sharing her desert knowledge, to alert us to keep looking and watching for the next surprising desert rain-gifts.