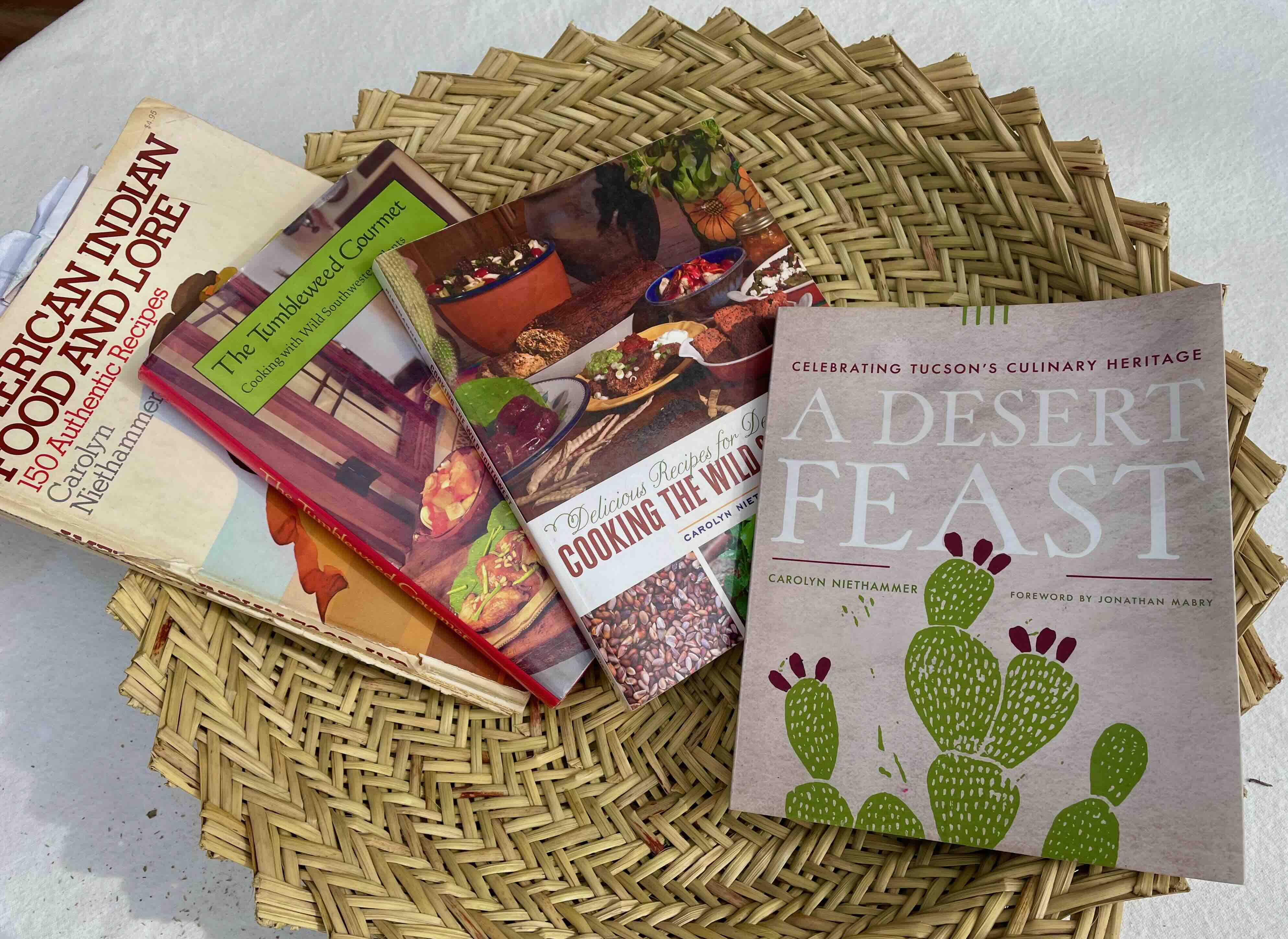

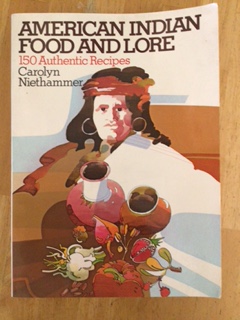

It’s Carolyn here today with a walk down memory lane. This year celebrates 50 years since the first publication of my first book American Indian Food and Lore, now republished as American Indian Cooking: Recipes from the Southwest. In 1970, I was a young out-of-work journalist and through an unlikely set of circumstances ended up with a contract for a book on Indian cooking with Macmillan, a major New York publisher. Preliminary research showed that traditional Native American food revolved around edible wild plants and corn, beans, and squash.

My college science was zoology so I had a lot to learn about edible plants. I began by reading every ethnobotany written about Southwestern plants. I found mentors to take me on plant walks, including the late renowned botanist Richard Felger. When I knew enough to ask intelligent questions, I headed out to talk to the experts, Native American women. My first teachers were two lovely Tohono O’odham women on the San Xavier section of the reservation who spent an afternoon teaching me to cook mesquite the way their mothers had. I put the leftovers in the backseat of my car and had a head-on collision on a narrow dirt road on the way home. Woke up in the hospital with mesquite mush in my hair.

Perhaps that was some sort of christening, so for $150 I bought a Chevy wagon and the summer of 1971, I headed to remote areas on the Hopi, Navajo, Zuni, Havasupai, and Pueblo reservations. Many very generous middle-aged Native women taught me about plants they had gathered with their grandmothers. I worked in an office that winter to gather some money and headed out again the summer of 1972.

Finding a communal grinding stone at Hawikuh (founded c. 1400) near the Zuni Reservation. Imagine the women sitting around the stone doing food preparation.

Then it was time to test the recipes when I had them and develop recipes when necessary. A friend lent me an electric typewriter (such a luxury), and I wrote up what I had learned. A small grant allowed me to pay Jenean Thomson to do the gorgeous and accurate line drawings of the plants.

The book was “in press” for two years and was released by MacMillan in 1974. Euell Gibbons had published several well-known books on edible wild plants, but they were all Eastern species. American Indian Food and Lore joined a very few popular books on edible Western plants. Sunset Magazine even came and did an article on my wild food gathering class. Writer and ethnobotanist Gary Nabhan joined me, and one year we did a class we privately called Gary and Carri’s Thorny Foods Review.

After two decades, with changes in ownership, Macmillan decided the book didn’t fit their line, but the University of Nebraska Press liked it. In 1999, they republished the book under their Bison Books line as American Indian Cooking: Recipes from the Southwest with a lovely new cover.

I have followed this title with four more books on Southwestern food, but my first foray into cookbooks with the all the memories I have doing the research remains a high point of my life.

Here is one of the original recipes taught to me by a Navajo cook.

Navajo Griddle Cakes

(Makes 14 4-inch cakes)

Although this calls for lamb’s-quarter seeds, you can substitute amaranth, quinoa, chia, or sunflower seeds.

¾ cup ground lamb’s-quarter seeds

¾ cup whole wheat flour

2 tablespoons sugar or honey

½ teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon baking powder

1 egg

2 cups milk

2 tablespoons oil or bacon drippings.

Combine dry ingredients in a bowl. In another bowl beat together egg, milk, and fat and add to dry ingredients. Heat the griddle and add a small amount of oil. Test the griddle by letting a few drops of cold water fall on it. If the water bounces and sputters, the griddle is ready to use. Bake the pancakes.

__________________________________

Note from SavorSisterTiaMarta: If you want to find other fascinating, flavorful, and from-the-earth Indigenous recipes that were gifted to Carolyn 50 years ago and which she published in American Indian Food and Lore, you can chase down used book copies via Thriftbooks, Amazonbooks and other sites. This first book is a treasure trove of totally useful, current ideas!