Elderberry (Sambucus nigra, synonymous with Sambucus mexicana) or tapiro in Spanish is a beautiful shrub that grows wild in many riparian places in the low desert of Arizona and Sonora, Mexico, or at higher elevations such as the sky islands of the Sonoran Desert and borderlands, in Europe, and beyond. In traditional/natural medicine, it has long been prized for its strong antioxidant qualities and is excellent for treating colds, coughs, and the flu. You can read many scientific studies like this Randomized Study on Influenza (Zakay-Rones Z, 2004) or Treatment of Upper Respiratory Symptoms (Hawkins, 2019) that have confirmed these benefits. The berries are not safe to eat raw or uncooked–but when cooked (at least 15 minutes to vaporize the harmful compounds), elderberry’s flavor is totally safe and naturally sweet.

Sister Emily here to share a popular immune-boosting syrup recipe made from this wonderful plant. I’ve harvested tapiro or elderberry from Tubac near the Santa Cruz River, on Mt. Lemmon in the Santa Catalina Islands, and near washes in the east side of Tucson. Also in Catalonia in Spain!

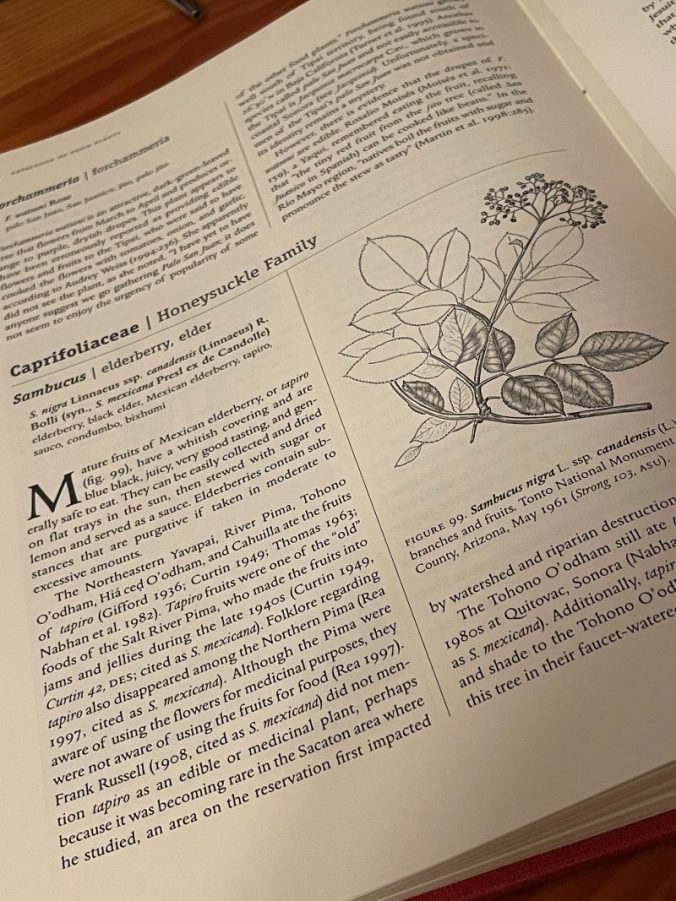

Dr. Wendy Hodgson’s excellent book “Food Plants of the Sonoran Desert” (pictured) describes the traditional uses of elderberry by the O’odham, Pima, Cahuilla, and Yavapai (Hodgson, 2001). Her research found that native people of the Sonoran Desert have always used elderberry fruits for food, medicine, and wine, and in some cases the flowers, too.

My Bulgarian musician friend says they prize the woody stems of elderberry for their long straight stems prized for making wood instruments.

Elderberry Syrup Recipe

I recommend keeping this delicious syrup medicine around all the time, or especially when the seasons change (to ward off colds and the flu).

Makes about 1 cup of finished syrup. (Ingredients can all be doubled for larger batches.)

Ingredients

- 1 cup dried organic elderberries OR 2 cups fresh wild-harvested* elderberries, destemmed and rinsed.

- 2 cups filtered water

- 1/2 – 1 cup raw, local honey**, depending on amount of liquid. Meet your local beekeeper at a farmer’s market!

Optional Ingredients:

- Herbs: 1/2-1 tsp. organic dried ground ginger, 1 stick of cinnamon, and/or a few cloves.

- Brandy or vodka- some people add 1/2 cup of either of these alcohols to further preserve the syrup and increase shelf life

*For foragers, always use caution to ensure you have properly identified the elderberry plant (Sambucus nigra or Sambucus mexicana), which is relatively easy.

**Do not feed infants honey.

Instructions:

- Combine elderberries (and optional herbs) with cold water in pot and bring to a gentle boil.

- Reduce heat and allow to simmer 30 minutes.

- Turn off heat and allow to slowly cool and steep for at least half an hour.

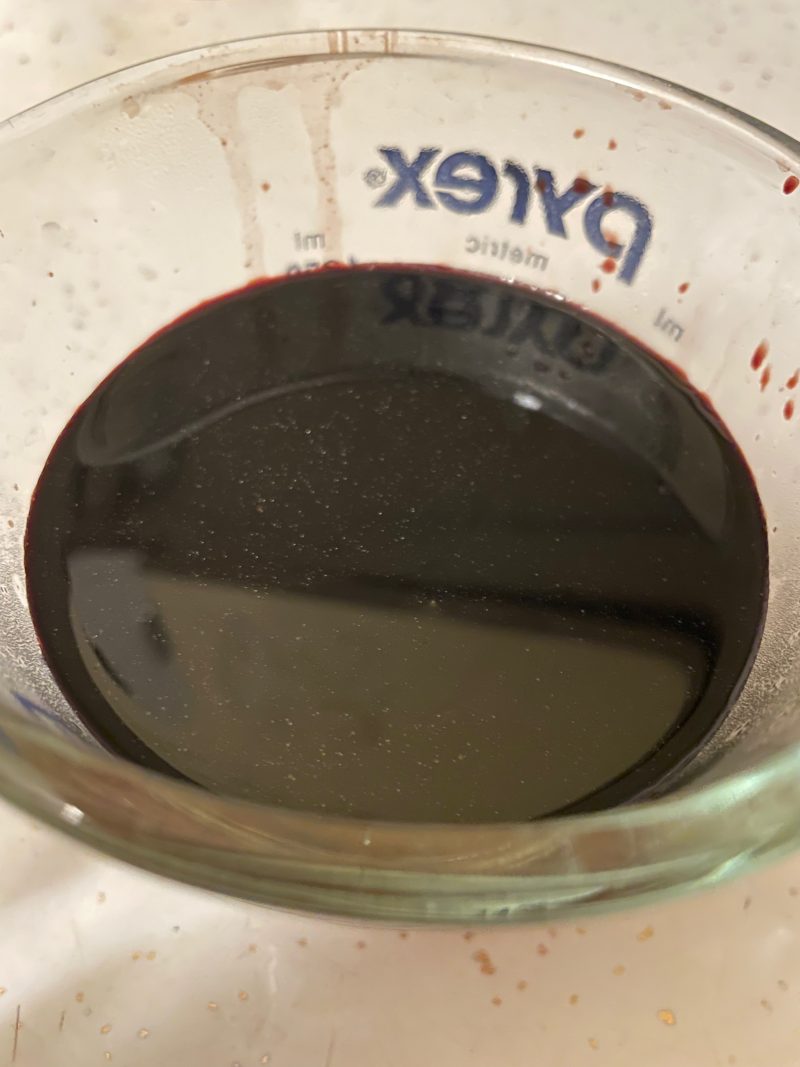

- Strain to obtain the elderberry liquid into a measuring cup. To capture the most liquid, you can also use cheesecloth or mesh cloth and squeeze out as much as possible of the cooled liquid.

Note: Don’t pitch those power-berries! The strained elderberries can be used as a immune-boosting topping for yogurt or oatmeal!

- Check the volume of the elderberry liquid. Check that you add honey in a ratio of half of this volume. (1 cup of elderberry liquid requires 0.5 cup of honey.) This will ensure that the syrup won’t spoil.

- Pour elderberry and honey back into the pot, and gently heat just enough to stir and incorporate the honey. (Heating honey too much will destroy valuable enzymes and beneficial antioxidants).

- Add optional brandy or vodka, if desired as an additional preservative.

- Pour into a clean glass jar and store in the refrigerator.

- Take a tablespoon (or two!) when you are feeling a little low or a bug creeping in, or just for a pick-me-up boost to the immune system. It’s also just a sweet treat.

Storage and Use:

This powerful syrup will keep 2-3 months or longer if stored in the refrigerator. I have also found my syrup to be stable (mold-free) for even longer, and tastes just fine! The natural preservative of honey is the key.

Want to make the syrup even easier? It’s hard to beat this very convenient complete Elderberry Syrup Kit from Tucson Herb Store on 4th Avenue in Tucson. Click to see this excellent option for purchase and included recipe by Ms. Amanda Brown.

References

Hodgson, Wendy C. Food Plants of the Sonoran Desert. University of Arizona Press, 2001. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv27jsm7t

Hawkins, Jessie, et al. “Black Elderberry (Sambucus Nigra) Supplementation Effectively Treats Upper Respiratory Symptoms: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trials.” Complementary Therapies in Medicine, vol. 42, Feb. 2019, pp. 361–65. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2018.12.004.7/147323000403200205

Zakay-Rones Z, Thom E, Wollan T, Wadstein J. Randomized Study of the Efficacy and Safety of Oral Elderberry Extract in the Treatment of Influenza A and B Virus Infections. Journal of International Medical Research. 2004;32(2):132-140. doi:10.1177/147323000403200205